Phase-ins: Not The Best Way to Manage Risk?

By Wade Witbooi, Retail investments analyst

The decision to invest a lump sum is generally the product of an extended period of saving, and investors take pride in their nest egg. Being human, investors tend to keep a close eye on their new investments in the first year, hoping that the promise of growth delivers sooner than expected, but more importantly, they dread seeing their savings decline!

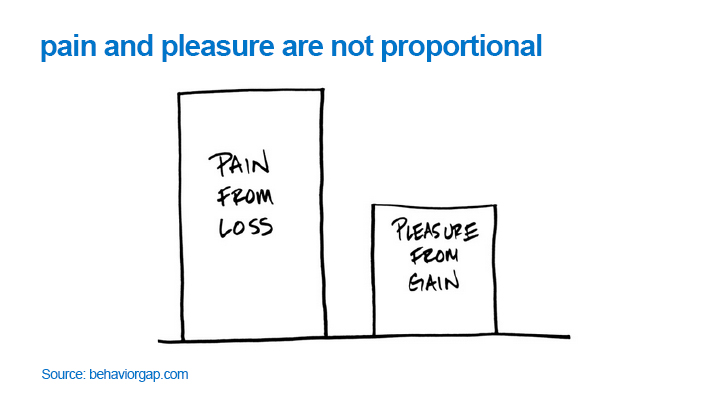

The initial emotional attachment to a new investment is the same for any new purchase, be it a new car, new sport equipment or expensive clothing. Behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman observed that humans typically experience the pain of loss with double the intensity than they experience the pleasure from an equivalent gain. This fear of loss is innate to all human beings and could lead to irrational investor behaviour.

Similar to taking great care when handling any new item until the initial concern of loss or damage wears off, investors sometimes opt for a phasing-in strategy of their investment to limit the chances of loss soon after investing. Phase-ins are attractive for emotional reasons. But do they, on average, do more harm than good?

What is a phase-in?

With a phase-in you first place your investment in a money market fund before committing it to a desired growth portfolio (with more risky assets) over a predetermined period (three, six or 12 months.) If you choose a three-month phasing period, for example, the capital is put in a money market fund and divided into three equal parts, which is then moved into the end portfolio month-by-month until the entire amount is fully invested in the riskier portfolio.

Why phase in?

If equity markets fall while most of an investor’s money is still in the money market fund, he or she will lose less money during that month than if they were fully invested in the more risky fund. This provides some comfort for investors. But if markets recover rapidly after the fall and the investor is still mostly invested in the money market fund, he or she will lose out on the gains during the recovery. The question remains: Does phasing-in add significant value?

What does the data show?

We asked one of South Africa’s largest LISPs about the most common frequency and duration of phase-in transactions. The feedback was that clients generally phase in monthly over six or 12 months.

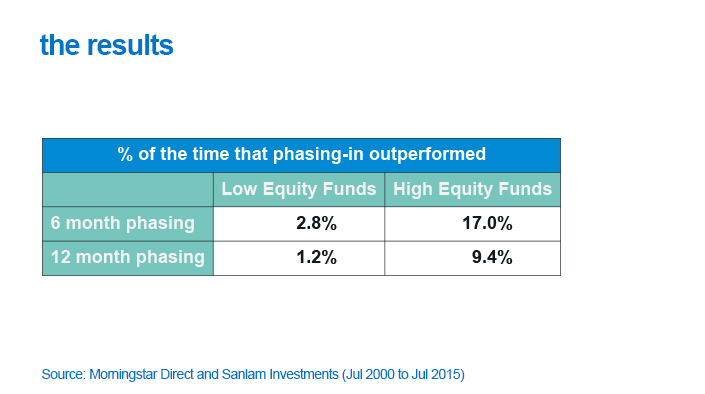

We then evaluated the phased returns (from July 2000 to July 2015) of the ASISA Low Equity and High Equity category averages (now the most popular categories) respectively over six and 12 months, versus directly investing into the fund.

How often did the phase-in strategy outperform? The result is shown in the table below.

Phase-ins come with an opportunity cost

A key advantage of phasing-in is that it can decrease the magnitude of the capital loss in the months when markets fall, provided that the market decline occurs during the first half of the phasing-in period. But it also has disadvantages, some of which are detailed below:

• a “cash drag” when markets are normal or trending upwards: Over the long term, for the majority of months equity markets are moving up – not down – and being in a low-yielding money market fund for too long drags down the overall performance of a portfolio.

• an altered client risk profile during the phase-in period: A financial adviser may have risk profiled the client as Aggressive, for example, but during the phase-in period the client will have the type of equity exposure associated with a Conservative risk profile, potentially jeopardising the client’s chances of meeting his investment goals.

The relative outperformance produced from a phase-in strategy is well below the relative outperformance of a direct investment strategy. A lower relative alpha combined with a low success rate makes a phase-in strategy even less likely to add value from a performance perspective.

The landscape has changed

Traditionally, phasing-in was one of very few tools available to limit capital losses during market downturns. There were not many established diversified portfolios to choose from to address perceived market risk. Investment product providers took it upon themselves to create a strategy to mitigate potential market risk, thus phasing-in was born. In essence, the investment product industry answered an investment management problem. But the industry has evolved with many new options for clients with different risk appetites.

And clients have welcomed these new offerings. The majority of new inflows are now going into well-diversified Multi Asset portfolios. With Multi Asset portfolios, the portfolio manager decides how much to allocate to each asset class. When equity markets are expensive, the manager will allocate less to equities, which decreases the investor’s chances of losing capital. For example, Multi Asset funds are currently highly exposed to cash, managing the risk of capital loss.

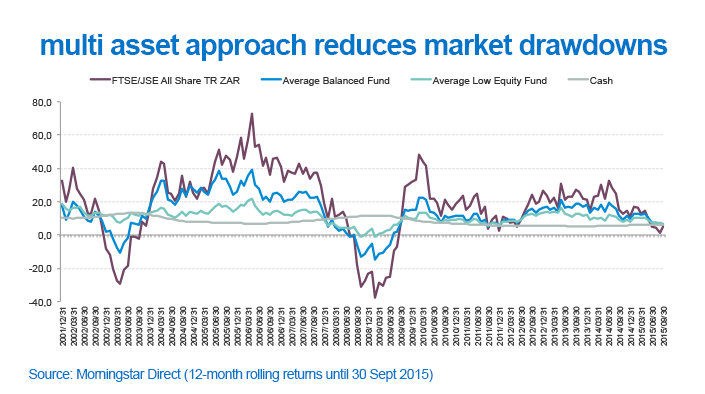

This Multi Asset approach to risk management is tried and tested, and the graph below shows how using Multi Asset funds (green and blue lines) have greatly reduced the magnitude of drawdowns that investors were exposed to relative to equity (red line) over the past 15 years (on a rolling 12-month basis). Naturally, the long-term returns of these funds will also be lower than equity funds. The point is: for risk-averse investors whose risk profile does not match a 100% equities portfolio, the asset managers are already managing the downside risk –phasing-in could potentially derail the strategy of the underlying investment manager.

Another tool to decrease an investor’s exposure to falling markets is the use of derivatives to hedge out at least some of the market risk. Funds that use this technique are normally a subset of the Multi Asset fund category. In addition to making asset allocation calls, they therefore also buy ‘insurance’ (through derivatives) against falling markets to protect investors’ money, while at the same time exposing it to growth opportunities.

A better alternative to phase-ins

The evolution of the industry has created opportunities for asset managers to offer products to minimise market volatility and participate in growth. Phasing-in is not investors’ only option anymore. As our client simulations show that phasing-in transactions have minimal tangible benefits, what would be a better approach for clients who are sensitive to short-term capital loss?

We would argue that it makes much more sense to choose the right portfolio manager or solution – one that manages your money according to your risk profile and invests fully in that solution from day one. We acknowledge that an investment entry point is a key determinant of returns, but trying to time the market is a futile exercise. Leave the asset allocation decision to the portfolio managers, who will reallocate capital to growth assets when they assess these assets to be cheap, or at least fair value. Then stay the course. This way you know your risk is being managed constantly – not only in the first year of investing.

Comments are closed.