How to invest meaningfully into Africa

By Todd Micklethwaite, Client Solutions and Research at Sanlam Investments

The opportunity set that exists in Africa presents investors with a sufficiently broad universe to bring positive, risk-adjusted benefits to institutional portfolios. But, investors should adapt those strategies which work in more developed markets to what works best on the continent. To capture the true investment potential that Africa presents, one needs to understand how best to execute an investment strategy on the continent. This has not always been the case with South African investors, and this is why.

African listed markets are even more illiquid than you think

African public equity markets are very different from their more developed peers with regard to accessibility, correlation to external factors and liquidity. Investors accessing listed markets are inhibited by the limited volume of daily trades, which opens them to the risk of particularly poor fund performance should investors require significant liquidity. This was seen from late 2014 through 2016, when as little as $75 million in stock was traded per day across the continent. An efficient fund manager may have been able to participate in 5% of that daily trade, but it would still have limited them to around $4 million in trades per day.

This limitation would have been exacerbated for larger funds; for those managers with funds that had grown towards $1 billion, this would have equated to an ability to trade less than 0.5% of their fund per day. As a result, it could have taken anywhere between 200 and 300 days to rotate or liquidate an entire fund. Investors in these funds learnt this lesson the hard way, with performance suffering to a degree from which many can possibly never recover.

Considering these risks, it is startling to note that most listed equity funds operating today have redemption terms shorter than fortnightly and, in many cases, daily! The risks of investing in a fund with anything less than quarterly liquidity are significant, with long-term investors unfairly prejudiced by the actions of those of a shorter-term mindset.

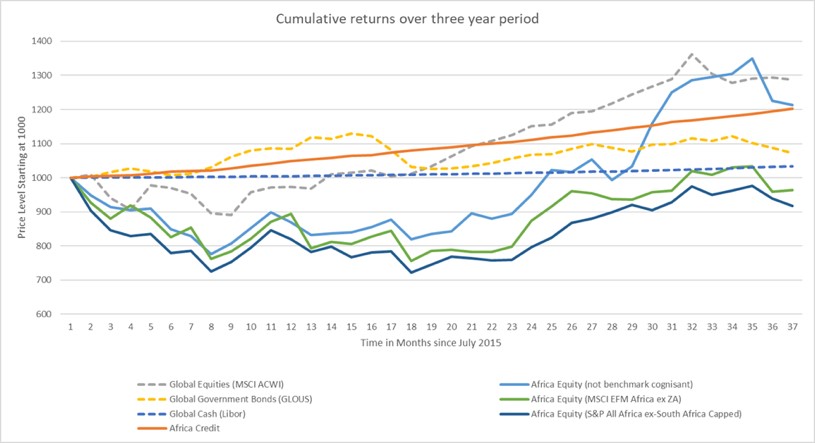

Seasoned African listed equity fund managers not only limit the capacity of their funds and have longer redemption and subscription terms, but they also broaden the scope of their mandate beyond the “investable” benchmark-cognisant universe. Where fund managers are not forced to invest with liquidity as a primary priority, more scope exists to find the best investment opportunities on the continent. Over time, benchmark-cognisant managers tend to run portfolios that more closely resemble the MSCI Africa, the 35 largest and most liquid stocks out of a universe of over 1 200. In Africa, the closet index managers tend to underperform their peers, often markedly, since Africa investing is very much a stock picker’s paradise.

But there’s more to Africa than just listed equity…

Across African markets, there is a significant discrepancy between the stocks listed on the market and those that are actually accessible to investors. Furthermore, the investable universe in even the larger markets is not a reflection of underlying growth in those economies. Investors therefore need to widen their net beyond listed markets if they want to capture the wider growth opportunities across the continent.

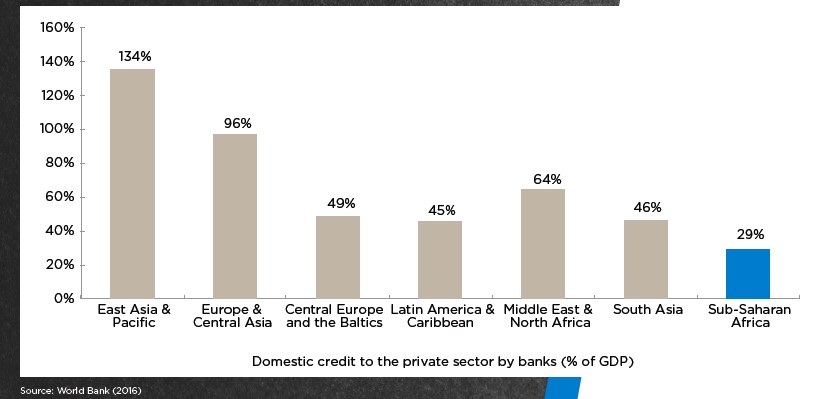

The case for investing into private credit in Africa is compelling. The International Finance Corporation estimates that the credit gap for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Sub-Saharan Africa is currently $70 billion to $90 billion per annum. This implies scope for an additional 300% in advances over the current estimated levels of loans being extended to this market. The opportunity in the region is attractive relative to its global peers.

The opportunity that exists for institutional investors is due to the dearth of finance on offer from local banks (that do not have the capacity to fill the gap) and the large international banks (which are increasingly steering clear of this sector due to their Basel III solvency obligations). Without taking on excessive levels of risk, investors are able to achieve US Dollar returns in excess of Libor plus 7% per annum on a consistent basis, by investing into African private credit.

The chart below shows historical returns for a relatively conservative African private credit portfolio alongside a range of other non-SA asset classes over a three-year period to 30 June 2018.

What does an allocation to Africa executed in this way bring to an institutional investor’s portfolio?

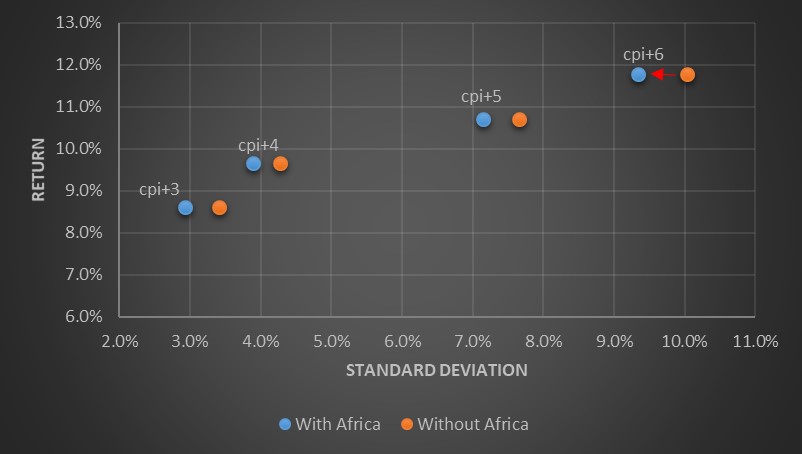

We built a model which uses a traditional mean-variance optimization methodology with long-term historical and adjusted forward-looking expectations for traditional local and global asset classes, and a correction for stale pricing present in African asset classes. For purposes of this article, only listed equities (unconstrained) and private credit were considered for inclusion in an African allocation. The negative and zero correlations exhibited by these African asset classes relative to the traditional assets led to their inclusion and to improvements in the efficiency of overall portfolios.

Source: Sanlam Investments, 2018

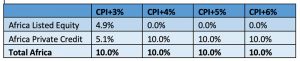

Our model found a definitive improvement in the risk of every fund that included Africa relative to the same targeted return profile. Notably, the diversifying characteristics of the African asset classes resulted in a maximum 10% allocation in each of the ‘optimal’ portfolios. Furthermore, the bias within the Africa allocation moved entirely towards private credit as the target margin above inflation increased (as reflected in the table below).

It is worth noting that, in addition to the risk-return benefits outlined above, an investment into private credit has liquidity advantages over its private market peers – the weighted average duration of the portfolio modelled was two years.

There’s more to ‘impact’ than infrastructure investment

Although investors have traditionally focused on infrastructure when a key driver for their allocation to Africa is the potential impact of that investment, many investors are identifying the critical credit funding gap as an equally noble cause.

It is certainly an honourable endeavour to support the growth of Africa’s capital markets and, equally so, to broaden the financial inclusion of Africa’s citizens. The inability to access debt capital is not limited to corporate entities and local banks, but also include micro-SMEs and individuals. Apart from funding institutional borrowers, private credit funds are indirectly able to assist in servicing the individual and micro-SME market by providing debt capital to reputable micro-finance organisations that operate in this sector. Unlike borrowing for private use in more developed markets, such borrowing in Africa is not used by individuals for consumption but rather to fund necessary expenditure related to housing, education, small-scale agriculture and small business.

Conclusion

As an African country, South Africa’s growth is inextricably linked to the continued development of the African economies and the communities with which it engages, and investors in South Africa have a critical part to play. Historically, investors have had few doubts about investing billions of dollars into assets outside the continent. Treasury has now opened the door further for investors to make an impact on the continent, where opportunities abound for earning attractive and consistent risk-adjusted returns.

Comments are closed.